Level 1. Catch Fire

It begins with a virus.

Then, after the apocalypse, you wake up in Boston.

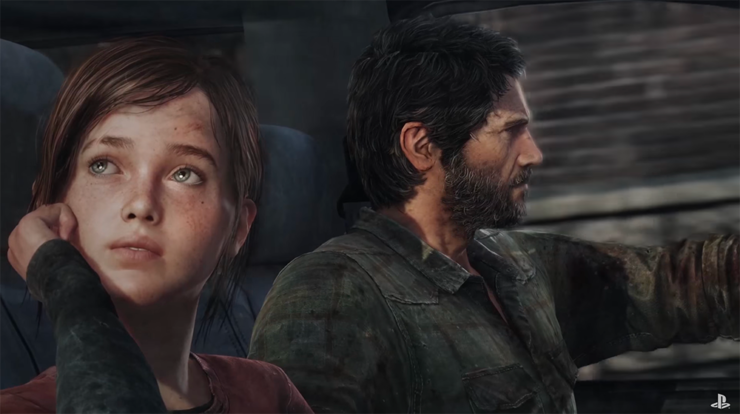

Leafless tree branches, pockmarked either with the white of residual radiation or mere silhouetted skeletons against a sky that is always the wrong color. Fog running along war-created riverbeds to hide mutated dogs and two-headed bear-wolves and zombies that run too fast. In the towns you happen across, people trying to kill you fill the alleyways between the brick apartment buildings. Military convoys rumble down concrete streets. Armed guards, dressed in the all-black of a steroid SWAT team or the rags of a band of marauders, swarm around concrete barricades. Storefronts are hollowed out, but occasional supplies will glow when you near them: scissors, gauze, ammunition for your .45; tin cans, the irradiated hide of an unnatural animal, ammo for your customized nine millimeter.

Shortly after returning home from a post-law school year spent starving in New York, I’d played The Last of Us Remastered for the PS4. As preamble to the exercise, I played through the original Gears of War. I wanted post-apocalypse in all its varieties.

My father had passed away over 18 years ago, and I was still angry. Genociding zombies with slapdash weapons across an irradiated America would help, I thought. I hoped. It was supposed to be fun.

My console hums to life.

* * *

Gaming is a break in the time-space continuum when I am hypomanic, and it is solace when I am clinically depressed. Seconds stretch and hours implode.

The worst feature of the often-enough promenades with the Black Dog isn’t necessarily the listlessness or the apocalyptic thinking, the doom-mongering that occurs when contemplating the self. It’s the cognitive fogging. When the disease contorts intent into a self-destructive posture, any attempt to think one’s way out of self-immolation fails. Venturing outside, forcing oneself to exercise or even to box, talking it out with others, sleeping through it, overworking, all of these become imported methods of manufacturing deliverance in the hope that if I can perform wellness well enough, then the charade will become reality.

When I’m too weak to do these things, I fire up the PS4.

Starting new games always induces a small episode of vertigo. Opening tutorials that walk you through the first level allow for varying degrees of wandering. If it’s a game like Gears of War, then you proceed straightaway with your on-the-job training. You encounter enemy Locust for the first time, learn how they move, whether they zig-zag, whether they leap at you on all fours. The bloodstained ground shifts beneath you, and you thrillingly surrender stability.

The same headiness fogs the brain when beginning a game of pogs or Monopoly, where the outcome is uncertain. Depending on one’s adeptness, the quickness of one’s mind or the celerity of one’s adaptive qualities, that headiness quickly gives way to clarity of thought. Muscle memory takes over and the ego dissolves, and one vanishes to self, swallowed by the world like after that first hit of cocaine.

Ultimately, however, the consequences are light. You, personally, don’t die. Only your avatar. The stakes are no higher than in a game of computerized chess or a game of dominos played against family members bloated and food-drunk from the midday Thanksgiving meal.

* * *

The Last of Us terrifies.

It goes without saying that no living human being will ever grab a fungal zombie by the throat and ram a shiv into the flesh just below its jawline while it thrashes in your arms. But it is conceivable that a living human being has rifled through the drawers of an abandoned home, in search perhaps of masking tape and scissors and rubbing alcohol, a rag, and maybe an empty bottle.

Ellie, the girl you’ve been charged with bringing across the country in The Last of Us, carries within her the potential cure for the plague that started the end of the world. The storyline—grizzled middle-aged, grief-hardened male ferries a teenaged girl across the American wilderness—is simple enough, but it is merely a skeleton upon which is draped the flesh, tendons, muscle, and organs of a brilliantly executed survival-horror game.

The game also lit a more primal light in my body, the same set of neurons fired up by gunning down aliens or enemy soldiers in a first person shooter. Only, instead of the thrill that attends the realization of invincibility, the heart trip-hammers in your chest at the subversion of that realization: you see, there were eight Marauders fanning out to circle the car behind which I hid, as well as a sniper in a house down the hill, my ultimate destination, and I only had three bullets to my name.

When your health depletes in the game, one of the only ways to get it back up is to use a med kit…that you fashion out of the rubbing alcohol and rag you found in that abandoned house you passed, the one whose former occupants left trails of blood on the floor and walls before dying off-screen.

In The Last of Us, enemies can attack you from behind while you pummel another with that beam of wood you found on the floor. A “Clicker” need only get close enough before you lose control, it bites into your throat, and the screen smashcuts to black.

Gears of War afforded me a genre of this feeling, but if those developers were Balzac, the men and women who made The Last of Us are Flaubert.

Survival-horror destabilizes in the extreme, and landscapes change, and new types of Infected appear, testing your degree of mastery. Always, you are recalibrating your actions to reassert stability. It was a small mercy when I’d made it to a cutscene.

What distinguishes The Last of Us from many games isn’t the abnormal intelligence of enemies but your avatar’s own limitations. You can only carry so much in your pack. Supplies come across your path rarely, your melee weapons deteriorate with usage, then break. And while Joel, your protagonist, punches like a kangaroo, he can always be caught from behind. And he is far from bulletproof.

A common sight among gamers, no matter the game, is the button-mash. When uncertainty overwhelms and calm flies out the window and muscle memory dissolves, the player’s fingers scramble over the controller or the keyboard, hoping and praying that out of the random discordant piano-playing, that beatifically ordered series of notes will erupt that will save the player from oblivion, guiding your Mario Kart race car back on course, defending your Sub-Zero from an oncoming combination attack, fleeing the Clickers who, at the sound of your struggle, have flocked to your position to tear you to pieces.

Game Over is the waterfall. And after a certain moment, you are powerless to stop your canoe.

* * *

My father was a child when the Biafran War began and still a child when it ended two and a half years later. According to an uncle, my father was a spy, a slightly removed child soldier. According to an aunt, the family was relatively sheltered under the philanthropy of white missionaries who had then descended upon them. It had not escaped the Western world’s attention that the besieged Biafran secessionists were Christian while the surrounding Nigerian government was Muslim, leaving aside the animism that distinguished strains of Igbo Christianity from the Nebraskan’s Pentecostalism.

It is entirely possible that my father escaped all of that, that his biggest inconvenience was that school would be cancelled for the war’s duration.

But when he was alive, I never asked him about his past as a child during the Biafran War or its dystopian aftermath. Nor did I ever ask him about marriage, his or the possibility, some day, of mine. And what lay inside of us to make us so antagonistic to domestic tranquility. Whether enduring war had anything to do with it. I wouldn’t know to ask him about that until he’d been dead for over twenty years. I don’t know if I have what killed him or if he had what I’ll be taking to my grave. But I have his blood in me and, one way or another, I’ll die as a result.

* * *

Level 2. Remain Indoors

I used to intersperse the more narrative-heavy games in my repertoire with hours of Fight Night: Champion, largely because I’d grown so accustomed to the game that my fingers moved over the buttons on instinct. The flash that preceded a perfectly-timed counterpunch was no longer anomaly. It was commonplace. I recently purchased Tony Hawk Pro Skater 5 because I’d needed a more innocuous gameplay experience than the meaty emotional meals I’d recently consumed.

Lessening the gravitas and the mortal outcomes, vicariously endured, that plagued my avatar, I could devote myself to memorized movement, a certain kinesthetic charge running through me, where the mind steps out of the body’s way, much like how I feel while boxing. Or, perhaps more aptly, playing the piano.

The plumber bouncing on the koopa’s shell is a new trill, the blue hedgehog collecting rings, spinning into a ball and crashing through enemies, an arpeggio. And even the littler personality tics that attend gameplay, the particular flavors of aplomb with which missions are completed and enemies demolished, become rivers of unthought. Moments where improvisation couples with joy, and neurons ejaculate into your synapses.

My younger brother, however, embraces games like Dark Souls and Bloodborne, hearty repasts salted with gratuitous difficulty.

We quest for the same endpoint. Faces flush with victory, we’ve mastered the thing. And yet I return to Fight Night not just for the balletic pugilism or the beauty at work in watching, participating in, expressions of glorious physicality pixelated on my screen. Not just for the blood or the catharsis of impact or any of the psychic rewards I get normally from watching a boxing match. But rather because doing something over and over and over again can be its own joy.

It is fun.

* * *

I spent a lot of time getting lost in The Last of Us. You wander, and, unlike in many other games, there is no indication of where to go when you run past the same vine-encrusted stone wall or walk through the same empty ski-resort cabin. Occasionally, there are characters you are meant to follow or the camera will swing in a particular direction, zooming in on your destination. Often enough, however, you’re meant to go where the enemy population is thickest.

It would have been much easier for this feature/bug of the game to frustrate me had not so much effort been put into the game’s art design. Even in postapocalyptic Boston, greenery abounds. The sun sets to give you the game’s own version of Manhattanhenge.

I played the Remastered version on the PS4 and among the upgrades was a higher frame rate, 60 frames per second optimized for 1080p resolution. Shadows are doubled, the combat mechanics upgraded, and the motion blur that occurs when turning the camera much reduced.

You see it in the motion capture, Joel tapping the watch his daughter has just gifted him for his birthday, the hoof prints left in the snow by the buck you’re tracking out west, the slowness with which bruises fade from your face, even the way the trash sits on the sidewalk.

From my very first playable moments outside, I knew this was the most beautiful game I’d ever played. By the time I’d made my way out west with my charge, the game’s gorgeousness had migrated from impressive to breathtaking.

Taking my horse around, I would go through already-explored rooms and corridors of a university campus, not because I’d gotten lost, but because I needed to see one last time how stunningly and bewitchingly these postlapsarian American cities had been rendered.

It happens on the faces of your characters as well. That complex twisting of features when emotions braid together and play themselves out in a twist of the lips or an arch of the eyebrow or the tilt of a head resting contemplatively against the palm of a hand.

I know precious little of game design, but I expect that no one involved in the creation and remastering of this game worked or slept normal hours. Lives may not have been destroyed in service to this cultural artifact, but marriages must have been strained, friendships ended.

All so I could shotgun a bloated, vitiated monster and watch it burst apart.

* * *

In this cutscene, I’m a child again.

During the fall, with our jackets and scarves, the family drives to Rogers Orchard in Southington. Dad puts me on his shoulders to pick the Red Delicious’s and Honey Crisps that no one else can reach. Granny Smiths are in season as well. Around us, baskets filled nearly to the brim with red and green. By the time we leave, I’m too besotted with the day’s haul to pay any attention to the apples that have fallen and rotted at our feet. They smell of honey, I remember somehow.

* * *

When my father died of chronic myeloid leukemia, he was 39 years old. I was 10.

The disease, as I remember it, was swift with him, far enough along when detected that it made short work of his insides and hollowed him out into unrecognizability. In the intervening years, he’s appeared in my memory of him in his hospital bed as more an apparition than anything else. I’d watched him turn into a ghost before his casket had been lowered into the ground.

Chronic myeloid leukemia was the first cancer to be explicitly linked to a genetic abnormality. Parts of the 9th and 22nd chromosomes switch places, or translocate. The BCR gene from chromosome 22 fuses with the ABL gene on chromosome 9. The protein that results is continuously active, requires no trigger, and stands in the way of DNA repair, rendering the landscape fertile for further genetic abnormalities to grow. There’s no determined, isolated cause.

Research on the heritability of mental illness is only slightly less inconclusive.

* * *

Genetic determinism is seductive. It is Greek in its tragedy. It is Biblical. Seen from a different angle, it is the theological paradox of free will. If God is omniscient, if predilection and proclivity are written into our genetic material, then what room is left for the individual, ungoverned by the external?

One theory put forward to combat, or perhaps complicate, the paradox of free will is the idea that God is somehow outside of Time. What we call “tomorrow” is His “today.” We have lost our yesterdays, but God has not. He does not “know” your action until you have done it, but then, the moment at which you will have done it is already His “now.” The descent into metaphysics and logical fallacies is steep and swift. Genetic artistry does not claim nearly the same sort of power over us. We can battle it. We can choose to battle it.

One controversial tool, as seductive as the doctrine of genetic determinism, is the discipline of epigenetics, or the idea that the life experience of previous generations has a say in the shape of our own genes. Did your rural Swedish grandfather from Överkalix endure a failed crop season before puberty? You might enjoy a higher life expectancy as a result. Did your parents witness or endure torture in a Nazi concentration camp during World War II? You might be in line for some stress disorders as a result. Pregnant survivors of 9/11 are alleged to have sometimes given birth to children with lower levels of cortisol.

Place a ball at the top of a hill, give it a slight push and see how it rolls, what valley it falls into. The world intervenes to guide its course, to turn straight paths knotty, to clear away brush or to erase formerly traveled trails. A breeze, an errant twig unearthed by a previous ball’s passage. Spores. Famine. Civil war.

The ugliness of unexplained difficulty makes epigenetics an enchanting proposition. Environmental factors switching genes on and off and affecting how cells read genes may help one understand or explain an affliction more easily than the dice-throw of a change in a DNA sequence. The pattern-making mammal wants to connect wartime trauma to the decision of the 9th and 22nd chromosomes to trade places. The pattern-making mammal wants famine and the thwarted ambitions of a nation that died in its infancy to explain why my father’s tongue was touched with fire when he sang Blessed Assurance during church services.

The pattern-making mammal has figured out how to time the throwing of his grenade.

* * *

Another cutscene:

We’re in a car, Mom and I. And we’re headed to New York City. During the drive down from Connecticut, I ask Mom if she’d been happy, married to Dad. The look on her face tells me that she’s never been asked that question, that she’s never been forced to consider it. Earlier in the drive, she had tried to counsel me on manhood, had dutifully pointed out all the incredible older men who had inserted themselves into my life as resources and role models. None of them had my diseases. Perhaps only Dad did. The more Mom spoke of those bits of him she saw reflected in us, my brother and me, those bits she struggled to turn us away from, the more I realized how absently I’d walked into my father’s being. Suddenly, I fit into the space he’d left behind, and I remembered various moments when I had become Mom’s affliction, the cause of so much sadness, her impetus towards prayer. When she spoke of how effortlessly Dad could charm light into a darkened room, I chilled with recognition. I had inherited his guile. And maybe I won’t ever know how much of him I’ve truly inherited until someone I love, someone I’m lucky enough to spend the rest of my life with, will tell me. Not in words, but in a sideways, forlorn glance or a sigh or in the effort it takes to hold back a sob.

In epigenetics is the opposite of prophecy. In epigenetics lies the promise that while I may have inherited guile and poisoned blood, that doesn’t have to be my child’s bequest.

* * *

The people who made The Last of Us had given me a gift. Had lost sleep and maybe even marriages, had possibly wrecked their bodies, flooded their bloodstreams with taurine, had fought through carpal tunnel. All so I could witness on my television screen a prismatic facsimile of my own blasted psyche, a post-apocalyptic cerebral landscape seen through a mirror darkly.

What is Ellie then?

Is Ellie the invisible hand of God made flesh? Is Ellie an environmental incident speaking softly to the world’s—to my—genetic material, over the course of this tour through a hallucinogenic alternate universe, injecting it with light? Changing its flesh?

* * *

The Last of Us was a game, but was it fun?

The breakthroughs in video games extend beyond the graphical. It’s not enough to marvel at the increased pixel count or the growing sophistication of a controller’s buttons and analog sticks. It’s not enough to note how consoles will now connect you to Netflix, to YouTube, to other gamers.

Conceptually, video games have evolved. We may have arrived at a stage of post-fun.

Games as a storytelling medium exist at a particular interstice. They are totems of participatory storytelling extended to the nth degree past Choose Your Own Story books. Forward movement arises out of the player’s decisions, yet, in the interests of storytelling, there can only be one direction in which to move. And the author, the game developer, knows this. Indeed, it is written in the contract.

Breakthroughs in any realm of artistry involve breaking; indeed, it is almost half of the word. Revenge against what came before. Romanticism in paintings after classicism, exiling straight lines to the land of the Dodo, uncaging emotion. Cubism after that. Grunge after hard rock. Flaubert after Balzac.

If one traces the genealogy of video games, the tectonic plates shift in similarly seismic fashion.

From the era of Donkey Kong and Sonic the Hedgehog, there came Mortal Kombat, where the fun lay in sanguine victory, after which came Call of Duty and the naked indulgence of the military-flavored power fantasy. And here we are now with mournful shooters and narrative-intensive survival-horror games. Games like Donkey Kong and Sonic still exist. Indeed, games moving farther in their direction, games like stoner opuses Journey and Flower, exist as well. But inherent in violence is the notion of consequence, and in a game like Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2, what does it say that you can willingly participate in a terrorist attack on civilians in an airport? Conceptually, imagining one’s place in the zombie apocalypse can be fun. You imagine you’d survive longer than you might. You figure yourself for more adaptive than you may actually be. But to embed that fantasy into a sorrowful story, a narrative bent on breaking the heart, is that fun?

So I ask again, was The Last of Us any fun?

* * *

Cutscene:

I’m old enough to remember physical sensations, to have bottled them and set up sentinels to guard them, yet young enough to be climbing on his shoulders. My cheeks are smooth, his stubbled. And I scale his back, arch my neck over his right shoulder (or is it his left?) and rub my cheek against his. He’s wearing a white tanktop. He shoos me away, but I cling tighter to him, and I’m smiling.

This is free, voluntary, devoid of serious consequences, not done in the normal course of father-son business; it’s unproductive, yet attended by the rules of the physical universe, skin and abrasion. And the outcome is unknown. Before I press my face to his, I don’t know for certain how it will feel, how much it will hurt, whether it’s a small enough price to pay for this particular genre of physical closeness.

We are playing a game.

* * *

Level 3. Lune

Maybe these games indulge some fury-driven shadow self. Maybe I revel in the violence. Perhaps it’s easy to see in the blasted earth of postapocalyptic America a simulacrum of my own psychic landscape. But it’s a destructive stereotype that automatically links violent people to violent games. Sure, there is some vent-cleaning involved, some power fantasy harmlessly engaged in. But why then do we want these games to provide us with meaningful stories as well? I can’t bring myself to believe that everyone involved in the creation of these cultural artifacts is a violent person or an enabler of violence. In smashing a brick repeatedly into a fungal zombie’s brain stem, maybe there’s more at work than bloodthirst.

Buy the Book

Riot Baby

The more stories and plays I read, the more movies I watch, the more my universe is expanded. It is increasingly true with video games as well. As with books and movies, video games offer a story into which one can read one’s own experiences. It is entirely possible that how you customize your character in Fallout 4, what clothes you dress him or her in or what scars or pockmarks you put on their faces, says something about you. It is also entirely possible that a preference for stealth over violence in The Last of Us says something about you too, but what it says may be impossible to know. Maybe only the gamer can ever know that.

In Gears of War, in The Last of Us, the loss of family is implicated. It is catalyst. The world is gone, and it took loved ones with it. We’re not trying to save the world, so much as trying to restore ourselves.

The pattern-making mammal in me wants to give credence to epigenetics, believing that if a single episode of emotional havoc can trigger illness, then some similarly marked event can initiate its reversal a generation later. I want a game to tell me that. I want a game to point me to him.

Press any button to start.

* * *

Epilogue

The developer behind the original Gears of War, Cliff Bleszinski (CliffyB), was born in Boston in 1975. In an interview, he confessed that he dreamed of that house he grew up in, on a hill, “basically every other night,” that Gears is essentially a homecoming narrative. There’s one portion of Gears that requires the player to get from the bottom of a massive hill to its top. On the way, Locust swarm. They flank you, and you scramble to find cover. Enemy fire comes from all sides as you tear and bleed and chainsaw and shoot your way to the top. Auras of invincibility give way to panic and terror and frenzy as your orphaned hero makes his way to that house on a hill. Where, as a child, he had known a father.